Christopher Damman, Associate Professor of Gastroenterology, School of Medicine, University of Washington. Editor-in-Chief of Gut Bites MD.

Ultra-processed foods have received quite a lot of press, and a bit of a bad rap, recently, and perhaps rightfully so. They’ve been linked to expanding waistlines, declining brain health, and even higher risks of cancer.

But what exactly is an ultra-processed food—and are they all equally harmful? How do they affect the body in such adverse ways, and what role might the microbiome—the trillions of bacteria and viruses living in our digestive tract—play in this process?

My name is Chris Damman, and I’m a professor of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, where I see patients and study the microbiome. I’m also a former Gut Health and Microbiome Program Officer at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, where I helped develop next-generation supplemental foods for women and children facing malnutrition.

The Forgotten Upside of Processing

We don’t often consider that food processing helped address hunger in many parts of the world and remains essential for famine relief today. Early nutritional science, understanding macronutrients like protein, fat, and carbohydrates, along with micronutrients such as vitamins and minerals, allowed us to prevent devastating deficiencies like kwashiorkor (deficient protein), pellagra (deficient vitamin B3), and scurvy (deficient vitamin C).

Modern ultra-processed foods grew out of this reductionist approach to food. And while the science initially helped address nutrient deficiencies, processed foods have since taken on a Frankenstein life of their own, meticulously engineered to co-opt our taste buds and reward pathways. The right combination of sugar, salt, fat, and flavor additives keeps us coming back for more.

What’s Missing Matters as Much as What’s Added

What’s less discussed is what’s been removed from ultra-processed foods rather than what’s been added. For every nutrient that’s concentrated, refined carbohydrates, sodium, saturated fats, there are missing components: potassium, micronutrients, fiber, healthy fats from nuts and fish, and phytochemicals like polyphenols from plants.

These missing ingredients are critical for both nutritional balance and for feeding our microbiome, which in turn supports our immune system, metabolism, and even mood. The health harms of ultra-processed foods arise not just from excess sugar or salt, but also from the absence of microbiome-accessible nutrients that whole foods naturally contain.

The Microbiome: The Missing Piece of the Puzzle

For decades, these “other” components—fiber, which give plants their structure, and polyphenols, which give plants their color—were thought to be unnecessary waste streams of food processing. But we now know they’re essential substrates for our gut microbes, which ferment fiber into short-chain fatty acids like butyrate and transform polyphenols into postbiotic compounds like urolithin A that regulate metabolism, immunity, and even mitochondrial function.

This missing microbial perspective has reshaped our understanding of nutrition: we weren’t just feeding ourselves. We were meant to feed our microbes too.

What Do We Mean by “Ultra-Processed”?

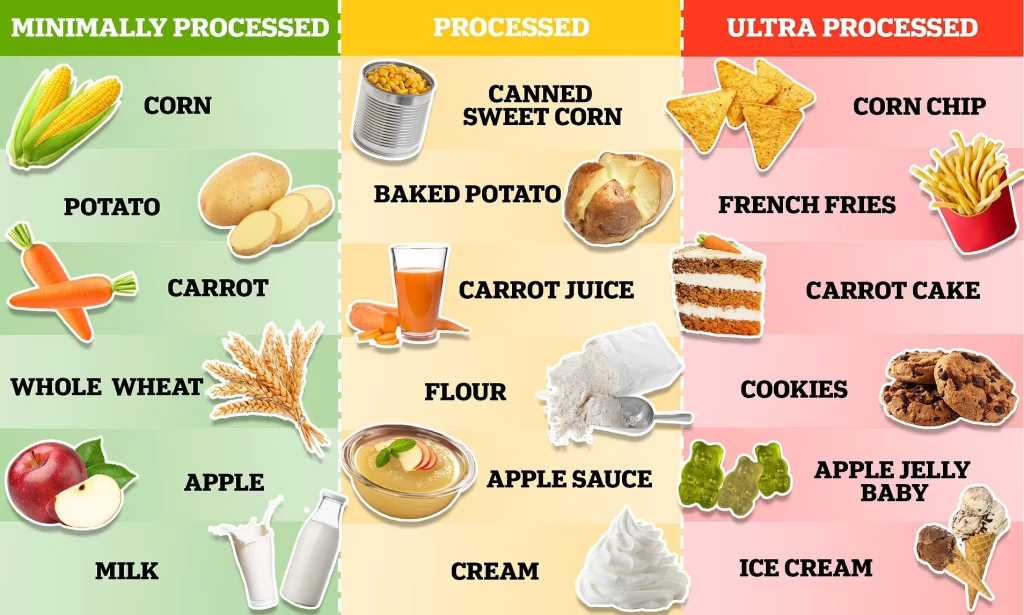

The term “ultra-processed food” was coined by Dr. Carlos Monteiro and colleagues at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, who developed the NOVA food classification system.

In short, ultra-processed foods (NOVA Group 4) are industrial formulations made mostly from refined ingredients and additives—sugar, starches, oils, protein isolates, and artificial flavorings—with few intact whole-food components. These foods are designed for long shelf life, convenience, and sensory appeal, not for microbiome nourishment.

Monteiro’s focus was on the ingredients added and intensified—not necessarily on what was lost. Yet the omissions may be just as harmful. Much like the macronutrient deficiencies of the early 20th century, today we face “microbiome nutrient deficiencies”—missing fiber, polyphenols, and healthy fats—linked to modern conditions such as obesity, diabetes, cancer, autoimmune disease, and neurodegeneration.

Can We Make Processed Foods Healthier?

Given the importance of processed foods for feeding the world, the question isn’t how to eliminate them, but how to make them incrementally better. The answer lies in restoring the natural balance once found in whole foods.

This means adding back fiber, healthy fats, micronutrients, and polyphenols—often lost as industrial waste streams—a practice now called “upcycling.” Ironically, our waste is becoming a new wellness commodity.

These reformulated products are not as healthy as whole foods, but they can be healthier than conventional ultra-processed ones, offering better nutrition, shelf stability, and flavor. After all, who doesn’t enjoy a good Oreo or bag of Doritos? The real question is: can we make a healthier Oreo or Dorito?

Empowering Consumers

Food companies are beginning to explore this space, but it’s difficult for consumers to know which claims: “Good for gut health,” “High in fiber” are credible.

Countries like France and Australia have introduced front-of-pack labeling systems such as Nutri-Score and the Health Star Rating to help distinguish better options. These tools work well for separating whole from processed foods, but they’re less effective at identifying the healthier processed foods within that category.

To address this, I developed a nutrient balance scoring system that targets the core nutritional imbalances in modern foods—ratios like sodium to potassium, carbohydrate to fiber, saturated to unsaturated fat, and artificial additives to phytochemicals.

This system has been integrated into a smartphone app that lets users scan foods in grocery aisles and see a score instantly. The hope is that widespread use will not only improve individual health, but also drive industry change by shifting consumer demand toward better products.

A Path Forward

Healthier ultra-processed foods may initially cost more and be considered an add on feature, just like power steering or power locks once did, but with scale, these innovations can become standard.

Just as we have significantly reduced nutritional deficiencies like pellagra, kwashiorkor, and scurvy, we can now address the microbiome-related nutrient deficiencies underlying many modern diseases—cancer, obesity, autoimmune disease, and Alzheimer’s.

With better science, smarter design, and informed consumers, even ultra-processed foods can evolve from part of the problem to part of the solution.

MD-authored gut health literature digests and first-in-class food quality app to power your microbiome.

MD-authored gut health literature digests and first-in-class food quality app to power your microbiome.

Leave a Reply